Portrait Photography tips

Original post>>>https://photographylife.com/portrait-photography-tips

As a photojournalist for 25 years and shooting for much longer, I may have a different or expanded definition of what a portrait is, and what it takes to produce them. There are genres of portraiture, of course, such as: editorial, corporate, commercial/retail, documentary or candid, and illustrative portraits. With some you exercise almost no control (e.g., William Albert Allard), and with others almost total control (e.g., Annie Leibovitz). There is no right or wrong answer … the photographer chooses their style! There are many photographers whose portraits I love, and not all of them are pure portrait photographers. Allard is a documentary photographer, but his found portraits are wonderful. Annie L. imposes her will on her subjects, but the results are fascinating and something I’d love to be able to do. If I were to pick my top 3 pure portraitists, it might be Arnold Newman, Gregory Heisler, and Annie L, in no special order. I went back and read my Arnold Newman’s “One Mind’s Eye” the other day, and was struck by how many of his images don’t use “perfect” light by today’s standards, but so many are amazing. This one, of Igor Stravinsky, is still one of the most brilliant photo portraits ever taken, I think. It’s interesting to know that Greg Heisler was one of Newman’s last assistants.

I have (too many) other favorite portraitists, for sure: Albert Watson, Mark Seliger, Mary Ellen Mark, Helmut Newton, Irving Penn, Avedon, Art Streiber, Dan Winter, Peter Yang, Brad Trent, and photojournalist Joe McNally, who is really a great generalist. I know I’m forgetting many.

There is one big factor in doing portraits: can you work with people? If not, shoot landscapes. I don’t say that to be a smart-aleck. People are tricky, sometimes a test, and to do portraits you need to be able to deal with all personality types. Shooting “found” portraits, documentary style, and literally introducing yourself to a total stranger, sometimes after they’ve seen you looking at them or aiming the camera, takes some courage. Don’t be afraid—in 30 years I’ve never been punched, and only threatened by criminals and psychos. If you don’t know the person, be polite, respectful, and just tell them you would be flattered if they would let you shoot their photo. It’s all about Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People” idea. When I see someone interesting out in the world, I just decide I am going to take their portrait and do it. There are some photographers doing some very interesting person-on-the-street portrait series in NYC, for example. Great stuff.

I like to talk more about other photographers, so I’ll start with that. Gregory Heisler might be the one I relate to and admire most, because his approach is that of a photojournalist and it’s so artful too. When possible, he tries to tell a story about that person either through environment (context), pose, location, and sometimes lighting. I say sometimes, because he never lets lighting be the predominant element in the photo, or overpower the subject. He is an absolute master and can light anything, and knows the secret—that less is often more. I want to pound on that point with a food analogy: If you take a fabulous piece of fresh fish, and over-season it with salt and pepper or garlic, the only thing your guest will taste is the seasoning. You’ve killed the delicate natural flavor, and the only thing you should ever do is try to enhance and bring out the best flavor of the food, sometimes very simply. One doesn’t always have to light a portrait (or you can’t) or not very much, or the natural light is better. “Available light is whatever is available”—and how good it is. Sometimes you need to add all the light, and sometimes just a kiss. If the first thing you notice when looking at a portrait is the lighting, something may be overdone. Heisler is the absolute master of this restraint, and I recommend his new book “50 Portraits” to everyone who wants to learn this. Don’t think that just because you’ve got this fancy strobe doohickey that you have to blast everyone you shoot (“if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”)

Here is one of my Heisler favorites, chosen for its masterful simplicity, its storytelling and its evocative mood, a portrait of boxer Muhammad Ali (who we know has Parkinsons Disease now). Heisler shot this in daytime, using the shutter and one well-aimed strobe to overpower the sun and create a somber scene, a powerful one of loneliness. He could have moved the camera closer to make Ali larger in frame, which I may have done if trying for a single image, but he’d shot other images tighter to complement this one. That’s something to remember … sometimes a portrait might actually be two images together, one tight to show their face, and one loose to show an environment. You always want the up-close or medium view too.

© Gregory Heisler

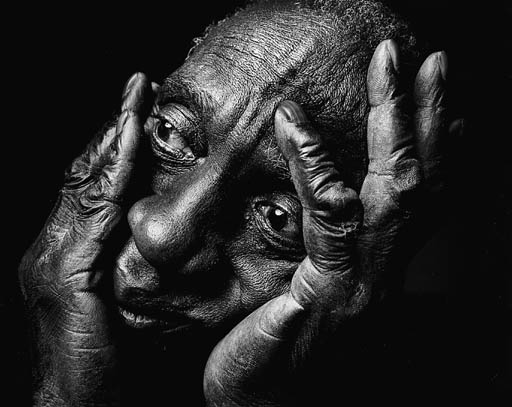

In this portrait of Luis Sarria, Ali’s masseur, Heisler takes the exact opposite approach— he moves in extremely close, and goes for a great face. Again – though he can light with 10 lights if he has to – in this case he used one light off-axis to sculpt Sarria’s face, to make him glow like burnished old leather. He decided that the story was his hands, those hands that had massaged Ali so many times, and the timeless face. Ultimate simplicity, the result being one of my favorite portraits ever. No background, no props, no context, no clothing—just the man.

© Gregory Heisler

Now I’ll get into my method. Nasim kindly invited me to write, after seeing my portraits including many celebrities. My process has often been the same as Heisler’s, but he, Annie L and others often have the luxury of making more choices like: location vs. studio; in character or not (for actors); props or no props; big setup or small. Shooting “normal” people, you have many more options and freedom. That’s a big plus! Actually, some senior portrait photographers are doing very interesting portraits of real people today, like magazine work. And by studio, I should say that anywhere can become a studio. Use your garage, living room … wherever. Use the props, and they can be anything. A studio is wherever you put up your lights. Wherever you are, get the lights off the camera and into the right spot.

The first, and for me most important thing, which I’ll discuss is lighting, because it’s always been a struggle. I can’t really get into the types of lighting here, or gear, because it’s a whole separate discussion—now we have a choice between strobe, hot lights, LEDs, Kino-Flo etc. Knowing the basic types of lighting (Google these) is good: pancake lighting, butterfly or Paramount lighting, split light, short light, broad light, rimlight, etc. You can find many examples of these in natural, found light. The discussion here on lighting is about doing it, and how much to do it, if at all. Lighting is a blessing and a curse—without good light you have crap, and if it’s crap you have to fix it. That said, “good” light isn’t necessarily perfect light or classical light, but maybe just interesting. Every great image of anything has some/all of these essentials: good lighting, composition, mood, storytelling, and moment/timing. Having to make the light good, especially in a large environment, can be a lot of work (and hard without an assistant) and often kills spontaneity or changes the mood and the subject’s responses. The big difference between a controlled portrait (where you set your lights and put the subject very precisely where you want them in the light) and a less controlled one where you may use one light or put them in the light you’ve found, is that you spend less time fiddling with lights doing the latter, and more time shooting. For that reason, a speedlight (or two, even three) set up to use TTL, can be a very fast way to achieve interesting lighting off camera without annoying or boring your subject to tears as they wait for you to set lights. Profoto just today announced a very exciting cordless monolight with TTL and 500 watt-seconds (think giant speedlight) which might be a super solution. Sometimes it’s just using a reflector. Sometimes just a large octo/box or umbrella to give a broad light source so you can maintain even light while your subject moves within an area. There’s a new trend among some photographers (e.g., Joel Grimes) to shoot almost HDR portraits, edge-lit hard from both sides, with the clarity and vibrance cranked up to 11, very pumped up. It’s not wrong and sometimes I like it, but to me in many cases it’s too much and needs to be used sparingly and judiciously I think. It’s a trend. I tend to go with a more classic look, but I’m old!

On countless occasions I’ve had to photograph celebrities or notables where time was extremely short. As in, 5 or 10 minutes from the time they walk in the room (often a hotel room—ugh). This is usually the case when you’re not Gregory Heisler! The funniest was photographing Kirk Douglas. He walked in, sat down in the chair I’d lit with one umbrella (having anticipated this), and gave me 5 poses as I shot 8 frames with the Hassy, then stood up and said nicely, “I think we’re done.” After sitting for 10,000 portraits, he was the boss. I had 7 decent frames, in 3 minutes! The worst was producer Steven Bochco, who kept me waiting for almost two hours and then stormed in and walked right up to my face and yelled “You have 30 seconds!” The photo was crap, and I was happy about that, perversely, because it was his fault. This has dictated and refined my working method to these steps/decisions:

- If I have 10 minutes, do I want to spend 2 minutes fooling with the lights, and 8 minutes shooting, or the reverse? (Sometimes you can have an assistant be your stand-in to preset the lighting).

- Can I shoot available light with few or no compromises?

- Can I include environment or do I have to go tight because it’s not there, relevant, or it sucks?

- How many images do I want/need? Can I shoot a tight shot and have time for something looser?

- How comfortable will the person be, and how much time will I have? This is often unknowable until go time.

The lesson in all this? Be adaptable, have a toolkit you’re comfortable with and good using (and that can be just one light or two, or a reflector), and pick the right tool for the job. Use the technology, like TTL for multiple lights, to make life easier for yourself. There are so many good gizmos for speedlights that there’s no excuse to make bad light. Heisler talks about having meticulously planned lighting schemes for a shot, only to throw it away and improvise on the fly. Use K.I.S.S. and learn what works without too much brain damage.

For this shot, of jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal, it was an ugly hotel room which he didn’t want to leave. I had my “strobist” light kit with speedlights on stands and umbrellas, as always. As I looked around the room, I saw light coming into the window that looked to me exactly like piano keys! All I had to do was place him in it (the “Do you want to light for 8 minutes or shoot for 8 minutes?” question). Yes, the light was hard but that’s OK … I cheated his face to look towards it a bit to get the shadows how I wanted them—I could have filled them but didn’t. He becomes part of a graphic composition but we see his face very clearly; it’s a medium shot.

For this shot of Forrest Whittaker, I wanted a gritty urban feel and he agreed to walk back in an alley downtown. I often like my subjects to make eye contact with the camera, but not always. In this case it creates a mood since he isn’t, so I had him look into the light (umbrella). One strobe in open shade, which is always a good trick even in sunshine … put your subject in shade and light them, letting the background go natural. Depending on the power of your light, you can ratio the brightness of them vs. the background easily.

Here’s another one-light solution, of comedian Richard Belzer. Lying on the ground in his driveway shooting up at him, I could only work one off-camera light by myself, but didn’t need more. I needed to overpower the sky to get it blue and rich. Simple works! Many portrait shooters will shoot at the end of the day using the low sun for their rimlight, and fill from the front with flash. That is a great technique – IF you can choose your time of day and location. Too often, I’ve not been able to.

Sometimes it’s good to work without a net. This day, I’d had it with lugging too much gear, and went on assignment with just one Leica M and a 35mm lens, Tri-X and a meter. When I walked in, rocker Graham Parker looked at me like “Where’s your gear, dude?” I sensed it, and said “Do you ever go unplugged, just acoustic? Well today I am unplugged.” He laughed, I looked at the room and got an idea. I took the lampshade off the floor lamp and asked him to pretend it was his microphone. He loved the idea, and sang a whole song while I shot this. Can you tell that I like the K.I.S.S. principle sometimes? I love shooting by fire and candlelight too.

Just one light placed on the other side of the door, framing this former Pullman Porter in the window of an old train car. KISS method again (are you sensing a pattern?)

I did this portrait of an 84 year old “macho” friend the other day, and wanted to light it a very specific way: old school. I don’t work in studio a lot because I like location environments, with information in them for context, but in this case I just wanted to concentrate on his face. it tells the story. I knew the lighting I wanted, and it was very specific and therefore he had to sit still, and all I had to do was capture the exact expression in his eyes. He says it’s the best photo ever taken of him, so I guess it worked! The downside to multiple light portraits, especially using small reflectors, grids, and dishes is that it can be so precise the subject can’t move much without changing the effect. In this case, it was all about textures … his beard, his skin, his clothes, and I lit for that. It’s the first one like it which I’ve done with the D800 and it blew my mind—I thought I’d shot it with my Hasselblad. I wanted classic, very straight light … beauty dish for Rembrandt light, reflector for fill, gridded light for rimlight. I don’t shoot like this as much as I should, because it inhibits me from trying different angles and compositions.

Here’s another, of a master woodworker, that had to be lit very specifically both for the furniture and for him… it can be tricky lighting people and products together because they have different needs. In this case I lit the desk first, and then adjusted the light for him once in the frame. I had to overpower the shop in the background as it was busy and ugly. It’s a three light setup (or four?) with a large parabolic brolly for the front, a gridded spot on him, and a fill light to camera right. It was all about adding shadow, texture, and form to the woodwork. Looks simple, but required a lot of tweaking.

Sometimes, all you need to do is put people in an interesting environment and then go with the flow. Shoot the portrait as the action happens around them. In this case I wanted to photograph playwright Luis Alfaro on the street in L.A., we picked a spot, and I said “Sit here please.” I just shot as people passed. (Mamiya 7 … sharpest lenses I’ve ever used. RIP).

I do some senior portraits, and here’s a recent one I like. I try to shoot in a no-gimmicks fashion—just great light, setting, composition, and color.

I love the “found” portrait, and seem to be doing a lot of them now. Some might quibble at that definition, but it’s really about finding people in interesting situations, and being able to capture them, with or without controlling the situation. This one is of two girls at the county fair late one night in the paddock. They knew I was there (with a 35mm lens) of course, and just ignored me after a time. The most important thing about this photo is that even though the light is green, I wanted it exactly as I saw it. Any light I might have added would have destroyed this image. So crank up that ISO, open the aperture, and brace the camera!

Here’s another portrait from the fair (and there are fairs everywhere), and as straight as can be. Open shade, soft light, and “Can I take your picture with your rooster?” Nice prop, that bird. I love this picture … so honest. Anything I might have done with it, like adding light, would have been moot or even ruined it. I didn’t ask her to smile, and usually don’t. This is with the D800, and the detail is amazing … would be a great 20X30.

Or this one, of a Hutterite boy. His parents said I could photograph him, but he was being coy and playing cat and mouse. I literally sat there until he turned for one instant, and I got one frame. There was no time to do anything except compose the shot and hit the shutter. It’s one of my favorite portraits, but a simple as can be— it didn’t need anything from me except to record it well.

Here’s one last found portrait. I shot this literally in a crowded restaurant, with my wife embarrassed and saying we were going to get kicked out. I was mesmerized by this guy’s red hair and his intensity, and the light, and so I just started shooting him as he sat and ate. Finally he looked at me with a “WTF?” stare, and I got my frame. Then I went to his table and gave them my card. He seemed very pleased with the attention once he saw I was a “real” photographer (and maybe not the FBI).

My next projects include a new series of B&W location portraits, and starting to experiment with using light-painting for portraits. Google ‘Dave Black’ as he’s a master of this and it’s very interesting. So many portraits to take, so little time. I feel like I’ve just scratched the surface and there are some very much more cutting-edge portraits being made out there. I need to push the envelope more – I’d love to shoot figure-study portraits too but I’m a coward (Google Micmojo … he’s amazing). I want a Fuji X100s for really low-key candid shooting and portraits. Happy shooting … don’t be afraid to go tell that total stranger you’d love to shoot their portrait.

Comments

Post a Comment

Please! Do not insert harmful link and hate speech.